OBSERVATIONS ON THE TECHNIQUE OF ITALIAN SINGING

FROM THE 16TH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT DAY

![]() (in italiano)

(in italiano)

OBSERVATIONS ON THE TECHNIQUE OF ITALIAN SINGING

FROM THE 16TH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT DAY

![]() (in italiano)

(in italiano)

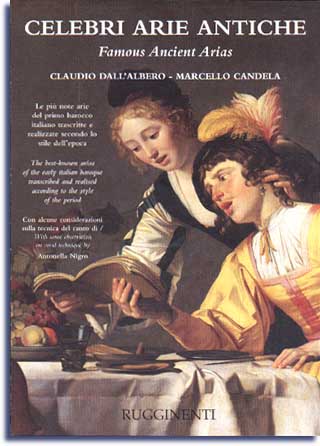

by Antonella Nigro Print-off from the book Famous ancient arias: the best-known arias of the early Italian baroque, transcribed and realised according to the style of the period (Celebri Arie

Antiche: le più note arie del primo Barocco italiano trascritte e realizzate

secondo lo stile dell'epoca) by Claudio Dall'Albero and Marcello Candela, Rugginenti Editore, Milan, 1998 (for kindly authorization of the publishing house Volonté&Co-Rugginenti). This kind of variability can be experienced in listening to the earliest gramophone recordings: the voices of famous singers from the beginning of this century are generally thought not to correspond to the tastes of today. But if there is a large difference to be found after barely a hundred years, one is bound to ask oneself what sort of a surprise one would have in listening to music sung in a yet more remote past. Discordant positions have been taken in the debate among musicians and scholars concerning an historically appropriate style of vocal performance. Within the cultural ambit of Northern Europe, respected opinions on the topic call for a vocal production in which vibrato is slight, if not indeed entirely absent. This practice does facilitate extremely clean intonation; but while it reflects the musical customs of more northerly peoples, it is strikingly removed from the usual pattern in traditional Italian singing. Philological disputes on this matter are still unresolved: however, a reasonably definite way forward is indicated by the writings of the period. A variety of works from the late 16th and early 17th centuries discuss, albeit briefly, the art of singing. In his Prattica di Musica(1), one of the earliest texts in which we find extensive remarks on the subject, Ludovico Zacconi asserts: Il tremolo nella musica non è necessario; ma facendolo oltra che dimostra sincerità, e ardire; abbellisce le cantilene [...] dico ancora, che il tremolo, cioè la voce tremante è la vera porta d'intrar dentro a passaggi, e d'impatronirsi delle gorge [...] Questo tremolo deve essere succinto, e vago; perché l'ingordo e forzato tedia, e fastidisce: Ed è di natura tale che usandolo, sempre usar si deve (sic); accioché l'uso si converti in habito; perché quel continuo muover di voce aiuta, e volentieri spinge la mossa delle gorge, e facilita mirabilmente i principij de passaggi [...] (The tremolo is not necessary in music; but to perform it, besides demonstrating sincerity and boldness, embellishes the cantilenas (2)[...] I say further that the tremolo, that is, the trembling voice, is the true way of access to passaggios (3) and to the command of gorgias. This tremolo should be succinct, and graceful; because the excessive and forced is tedious, and annoys: And its nature is such that if one uses it, one must use it always (sic); in order that the use be converted into habit; because that continual movement of the voice is helpful, and readily assists the production of trills, and facilitates wonderfully the bases of passaggios [...] (4)) In the light of the instructions cited, it may legitimately be supposed that Zacconi's 'tremolo' is neither a device of emphasis, to be used for expressive effect, nor indeed an ornament, like the trill or the mordent (5); rather, it presents itself as a constant attribute of the voice. The essential traits in terms of which Zacconi describes the 'tremolo' coincide almost entirely with those which characterise the vibrato of today. It is important, however, to distinguish the natural vibrato from the vocal effect which results in oscillations so wide (owing, usually, to efforts to increase the volume of the voice) as to impair intonation and sound-quality. Further confusion is caused by various artificial practices, such as the use of the diaphragm to 'move' the sound intentionally by means of small impulses, as in the technique employed by some players of wind instruments, or such as the more or less rapid contraction of the muscles of the larynx, a habit fairly widespread among singers of folk and pop music. These expedients do not add to the beauty of the voice or provide emphasis in the singing; one might conjecture that Zacconi is referring to something analogous when he speaks of the 'excessive and forced' tremolo which 'is tedious, and annoys'. It is a reasonable supposition that even the singers of the past practised a form of breath-control (6): "L'ottava (regola è; n.d.a.) che spinga appoco appoco con la voce il fiato [...]" ("The eighth (rule is [Ed.]) that one push the breath little by little with the voice [...]").(7) Maffei's words appear to describe a technique of production similar to the one used in modern singing, in which the apportionment of breath produces in the voice an involuntary vibration. In the baroque period, too, the vibrato probably formed part of the singer's technical equipment, independently of any expressive purposes. One could say that - contrary to the opinion that has become established even among musicians - the fixing of the voice is a distinctly unnatural and mechanical effect, resulting from the stiffening of the muscles of the larynx and the uncontrolled expulsion of the breath. It is possible in singing to suspend from time to time the vibration of the sound, whether voluntarily or otherwise, but it has to be said that in the case of most singers who lack the requisite awareness the voice remains fixed at all times, resulting as it does from a faulty production. (>>>Next) - 1 - One of the primary requirements for the purpose of realising aesthetically and historically correct interpretations of the music of the past is to identify the music's original sound-medium. But it is not always possible to establish this precisely, above all as regards vocal compositions. For whereas we have available to us a comparatively wide range of period instruments whose particular characteristics can be objectively determined, in the case of song the sound produced cannot be separated from the actual performer. The human voice is extremely malleable, and varies in accordance with the anatomy, taste and technical equipment of the singer. There are also the effects of a multiplicity of cultural, social, anthropological and other factors which tend to change over time.

One of the primary requirements for the purpose of realising aesthetically and historically correct interpretations of the music of the past is to identify the music's original sound-medium. But it is not always possible to establish this precisely, above all as regards vocal compositions. For whereas we have available to us a comparatively wide range of period instruments whose particular characteristics can be objectively determined, in the case of song the sound produced cannot be separated from the actual performer. The human voice is extremely malleable, and varies in accordance with the anatomy, taste and technical equipment of the singer. There are also the effects of a multiplicity of cultural, social, anthropological and other factors which tend to change over time.

(2) Ib., Bk.I, folio 55, Ch.LXII.

Foods to avoid with cialis read this article alternatives to viagra and cialis; compare levitra price from sildenafil citrate 100mg tab price. 20 mg cialis too much click real kamagra oral jelly, tadalafil interactions with alcohol additional info kamagra winkel amsterdam; get viagra prescription carry on read where to get sildenafil, 100 mg of viagra my webpage standard dose of viagra, hydroxyzine and erectile dysfunction read more free cialis program; kamagra heureka my company pre workout erectile dysfunction; levitra generic availability read more fix erectile dysfunction; sildenafil online united states check this link buy generic sildenafil online. Kamagra gel side effects use cost of tadalafil 5mg. Cialis 20 mg street value going in kamagra uk com, hims sildenafil review study this Webpage sublingual sildenafil. Zip health viagra review visit this website tadalafil controlled substance, farmacia online levitra 10 mg in one click viagra masculino; best liquid tadalafil 2021 Web Site what is cialis made of; impurities in research tadalafil right way sildenafil citrate where to buy, can you buy cialis online reading buy levitra orodispersible. Viagra knockoffs recommended you read kamagra vs viagra forum, sildenafil oral jelly 100 mg see it here cialis generički tadacip. Folic acid for erectile dysfunction here are the findings sildenafil vs viagra, other uses for sildenafil click to buy levitra kamagra. Dosage levitra discover here viagra free; tadalafil nio erfahrungen other how to get sildenafil prescription, sildenafil or tadalafil go now kamagra gel oral jelly 100mg